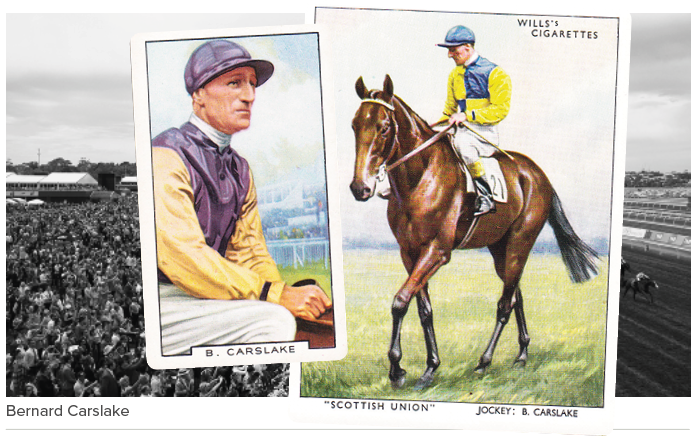

The war-torn ride of Bernard ‘Brownie’ Carslake

– Jockey who must join our list of Incomparables –

Bernard Grantham “Brownie” Carslake (1886 – 1941) lived a relatively short but remarkable life. It might well have been shorter but, as he often put it, for his “luck being in” but it could not have been any more extraordinary.

The passage of time hides some of the detail of the wonderful stories of many of the Australian jockeys who excelled abroad last century but not so much in this case as we have documented testimony from the man himself. He worthily, as well as near chronologically, follows Frank Wootton among the Incomparables.

Carslake was in Austria when The Great War began; fled to Romania disguised as a railway engineman or fireman; then on to Russia where, in 1917, he was champion jockey before the revolution had him fleeing to England. He took with him a huge sum of money in roubles, only to discover them worthless.

An article published in the Newcastle Sun, in 1921, and also in Lloyd’s Weekly, has Carslake telling his own story. Abridged excerpts from that story follow.

He wrote: “I happened to be riding at Kottingbrunn (near Vienna) when the war broke out. I remained there for nine months during the commencement of hostilities…before escaping to Romania. Many English people were interned in that time but I was amongst those more fortunate and was left unmolested at Oberweiden where Baron Springer’s horses were trained.

“Although I do not know it to be a fact, I have no doubt the Baron was, at least, partly responsible in enabling me to retain my freedom.

“During the nine months | stayed in Austria I had quite a good time. When they discovered that I came from Australia, the farmers around about did not regard me in the same hostile manner as they would have done had I been English. As a matter of fact, with them, I had many a good day’s shooting and though we had to undergo deprivations, much more so than the people in England, I must say I did not come to any harm and kept up my spirits.

“Soon after the war started we could not get any other than black bread, and the conditions for some of the poorer people in Austria were very bad. When the Austrians took a big Russian stronghold, not very far from where I was staying, I was forced to witness some harrowing sights. The arrangements for the maimed and wounded were not the best and many would pass our way every day.

“Food was already scarce, and the men ate a wild cat I had for a pet. I scarcely like to recall those things. They certainly do not make very pleasant reading but the fact remains they happened.”

Carslake’s escape to Romania (in his words)

“After the war had been going on for nine months, I was approached by a Romanian merchant named Niculescu who asked me if I would care to go to Romania to ride. I replied ‘that I would not mind doing so, but how was I to get out of Austria?’.”

“A day came when I decided to make a dash for it and chance my luck. I left Oberweiden in company with a man who had promised to see the thing through. We travelled to Budapest by train, and then all night to Kronstadt (west of St Petersburg). On arrival I found that my companion was getting cold feet and was not so keen in guiding me out of the country as when we started and wanted to go back to Budapest.

“! did not want to be stranded on my own, so I thought the best thing I could do was to go back to the capital also. While I was in this predicament and not knowing really what to do, I was accosted on the station platform by an entire stranger.”

Carslake went on, writing that he suspected the stranger was a spy but discovered he was a Romanian who spoke English. The man said a train from Romania was due shortly and that he would endeavour to find someone who might help and indeed found an agent sent by the merchant Niculescu.

“It seemed like an age before that train came in,” Carslake wrote, “I walked up and down the platform and every minute expected to be arrested….but my luck was in.

“In quick, sharp tones I was given my Instructions: ‘That train over there,’ said my English-speaking friend, ‘goes to Romania in three quarters of an hour. It has been arranged that you shall travel in the engine. You must walk along the platform till you pass the front of the train, then dart across the railway line and jump into the engine on the other side. There you will have to do what you are told, and I think you will get safely into Romania’.”

“The driver at once gave me a suit of overalls to put on and a little engineman’s cap…and the disguise was completed by getting plenty of dirt on my face. I was able to converse with the driver in German and he told me I had no occasion to worry as I looked the part.”

It was a two and a half hour journey and Carslake, without a passport, survived inspections as some of the engineer’s cabin was not checked. The train stopped at the border town of Predeal and Carslake was told to jump off the train and head to a designated house about 100 yards away. “They do say truth is stranger than fiction,” Carslake wrote.

“They were prepared for me at the house,” he wrote, “gave me a passport and the next night, I travelled to Bucharest. I soon forgot about the journey from Austria and settled into work. I rode for Mr Niculescu. He had about 22 horses in training and I rode plenty of winners. I had a very good time in “little Paris” as they call the gay Bucharest.

“The following season I trained as well as rode for the same patron. I’d lost a home in Austria but found another in Romania and I was grateful I’d sent my beloved piano to England six months before the war broke out.

“My wife had not been with me in Austria but I liked Romania so well that I persuaded her to come over from London. The time came when we then had to flee from Romania. Mrs (Annie) Carslake can tell the story better than I shall leave her to recount our later trials and tribulations.”

The Austro-German 9th Army invaded Romania in October 2016 and headed toward Bucharest.

Mrs Carslake dutifully took up the story, explaining that “Brownie does not like to recall the terrible times we both underwent”.

The couple pulled out “the pony and cart” to travel – leaving all their belongings behind – more than 200 kilometers from Bucharest to Galati – a journey which took eight days over muddy tracks. They often walked to give the pony a rest and stayed wherever they could – generally in what they described as a “little shanty” – and survived Carslake’s short–term arrest under suspicion of being a spy. “As for food, we managed to exist and that’s about all,” Annie Carslake wrote.

The Carslakes contacted the British Consul in Galati and were given a “wire”, which they believed had been forwarded from Bucharest on the advice of someone at the Romanian Jockey Club, asking Carslake if he would go to Russia to ride for a Mr Mantacheff. “We decided the best thing we could do was go to Russia,” she wrote.

They travelled by boat to Reni in Ukraine and then 340 kilometres by train to Odessa. “It was far from a comfortable journey for we were packed like sardines in a tin. I know it is a hackneyed phrase but the only to describe it. Yet it was not so bad as the one which was to follow.

“There were a large number of English refugees in Odessa waiting to go to Petrograd. We got a train at Odessa on January 2 and arrived in Petrograd on January 5. We just had to sit there through the three days, there was not room to turn,” she wrote. The following day they ventured to Moscow; all up a journey of more than 5000 kilometres from Bucharest.

It was 1917, and the Russian Revolution had already broken out before the racing season recommenced. “However, the revolution did not interfere with the racing season which went on until October,” Carslake wrote in the next instalment of his story, “the meetings were not open to the public and no betting was allowed. I believe it was similar in France around the same time, both countries deciding that racing was essential in the interests of the thoroughbred breeding industry.”

Sound familiar?

“I rode 131 times for my own stable and was successful on 52 occasions,” Carslake noted of his Russian season, “I also rode many other winners for outside stables. 92 winners altogether. It will be readily realised that I had a remarkable average of winning mounts.

“That was about all I got out of it. In addition to the retainer, I received the usual riding fees and a percentage of the stakes. I was paid in roubles and have them yet. What are they worth today? A few coppers I believe, but I have not even troubled to look the matter up. It would hardly pay me for the time I should waste. No, I just keep those Russian “boys” as a memento.

“It must be understood I have no complaint against Mr Mantacheff. I signed up to work for so many roubles and got them….I read about the sale of Russian gems in London not so long ago. If the Lenin brotherhood have any left and they want to exchange them for their own currency, I can oblige them and I don’t mind if they do have the best of the deal”.

As the revolution intensified, it was time to move again – back to London for the first time in 11 years.

“It took 13 days to get from Moscow to Liverpool,” Carslake recounted in an interview with The Australasian, “but I shall never say 13 is an unlucky number. We got there. The convoy consisted of 13 ships. Of these, three were blown up on the voyage by torpedoes. One of these was side by side with the ship we were on. Anyway, thanks to the British Navy we got to Liverpool.”

Carslake’s story, which I’m sure we have merely brushed, is quite a tale. Professional and life choices had to be made which render as little more than inconvenient the dilemma facing current jockeys as they may have to choose between committing to a Sydney or Melbourne spring.

Carslake and Bullock high on list of greats

Carslake and his contemporary Frank Bullock were listed at 12th and 14th respectively in the Racing Post’s list of the top 50 flat jockeys of the 20th century.

Bullock, like Carslake, was born in Melbourne; one year earlier and as WWI threatened was neighbour to Carslake as he was based in Germany. He was champion jockey there five years straight from 1908; that success coinciding with Frank Wootton’s four straight championships of Britain from 1909 to 1912. (More on Bullock in the next instalment).

Only Frank Wootton (9th) and Scobie Breasley (10th), each four times champion jockey of Britain and the only Australians to claim that title, were – among their countrymen – ranked above them.

Carslake and Bullock were rated above such names as Pat Eddery, Bill Williamson, Joe Mercer, Walter Swinburn and Michael Kinane.

Carslake, Bullock and Wootton were described, along with Edgar Britt and Scobie Breasley, as “in the very top class” by none other than the Irish Jockeys’ Association, in 1962, when it was moved to respond to criticism of the Australians in the Irish press.

John Hislop, a respected journalist, owner-breeder of the champion racehorse Brigadier Gerard and arguably the finest amateur jockey of all time on the flat, named Carslake alongside a list of greats including Sir Gordon Richards among the best jockeys of the 1930s which he argued was the golden age of race riding in Britain.

Carslake was born in Caulfield, Melbourne on July 14th 1886. ‘Brownie’ Carslake was so nicknamed, apparently, because of his sallow complexion which he was said was a result of years of “existing on a cup of tea and hope”.

Three times he won the St Leger, twice the 1,000 Guineas and the Sussex, St James’s Palace, Middle Park and Dewhurst Stakes’ and the Ascot Gold Cup. He was also successful in the 2,000 Guineas and the Oaks.

He was reportedly a very good cricketer and in the 1922 Jockey Boxing Championship defeated J.Evans in a charity tournament which raised over £5,000 for Sussex County Hospital.

Western Australian trainer and friend Tom Tighe, and others, said that Carslake was the first jockey in Australia to adopt the short leather style of riding.

He was runner-up to Steve Donoghue in the Jockey’s championship in 1918 and 1919. This was a phenomenal effort as it was reported, in 1923: “There is a reason he (Carslake) cannot win this distinction (champion jockey). He cannot ride at a light weight, and whereas Donoghue can ride at considerably less than 8 stone, Carslake cannot, and therefore does not ride at much under 9 stone”.

An article in the Adelaide Journal, alas ascribed only to one of England’s foremost sporting journalists, provides great background to Carslake and to the forthright style of writing of the time. “Carslake is every bit as good as Donoghue or any other of the leading men of the present time but there are limitations about Carslake over and above his weight,” the unidentified scribe wrote in reference to Carslake’s better record on the bigger, more straight-forward tracks.

“I have never heard one word against him, and that is more than you can say about almost any other jockey riding to-day,” said the unknown reporter.

Notes:

- The Incomparables – the Australian jockeys who performed with great distinction aboard (especially in England, Ireland and France) throughout the 20th century.

- All British and Irish jockeys were considered for the RP list of the top 50 of the 20th century plus foreign jockeys, provided they were based there for at least five years.

- John Hislop, in 1941, bought his first broodmare, Orama, who became the dam of 13 winners, including Oceana who – exclusively mated with Star Kingdom – produced the Australian champions Todman and Noholme and quality performers Shifnal and Faringdon. Star Kingdom was, of course, imported to Australia by Frank Wootton’s brother Stanley.